The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 17

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 17

Letter, Pleiades Club Yearbook, 1918

No nation as yet

The only sensible way

Seldom has the great art

Breadth is useless unless

A man possessed of an idea

I count on seeing

Be a warhorse for work

Ways of Study

I find nature

1.

Letter

Pleiades Club Yearbook, 1918

I have no sympathy with the belief that art is the restricted province of those who paint, sculpt, make music and verse. I hope we will come to an understanding that the material used is only incidental, that there is artist in every man; and that to him the possibility of development and of expression and the happiness of creation is as much a right and as much a duty to himself, as to any of those who work in the especially ticketed ways.

There is much talk of the “growth of art” in America, but the proof offered deals too often with the increase in purchases. I’m sure it often happens that the purchaser believes he has done his art bit for himself and for the public, when he has bought. Being a struggling artist myself, far be it from me to say he should not buy! But buying is not enough. We may build many imitation Greek temples and we may buy them full of pictures, but there is something more—in fact the one thing more which really counts before we can be an art nation—we must get rid of this outside feeling of looking in on art. We must get on the inside and press out.

Art is simply a result of expression during right feeling. It’s a result of a grip on the fundamentals of nature, the spirit of life, the constructive force, the secret of growth, a real understanding of the relative importance of things, order, balance. Any material will do. After all, the object is not to make art, but to be in the wonderful state which makes art inevitable.

In every human being there is the artist, and whatever his activity, he has an equal chance with any to express the result of his growth and his contact with life. I don’t believe any real artist cares whether what he does is “art” or not. Who, after all, knows what is art? Were not our very intelligent fathers admirers of Bouguereau, and was not Bouguereau covered with all the honors by which we make our firsts, and were they not ready to commit Cézanne to a madhouse? Now look at them!

I think the real artists are too busy with just being and growing and acting (on canvas or however) like themselves to worry about the end. The end will be what it will be. The object is intense living, fulfillment; the great happiness in creation. People sometimes phrase about the joy of work. It is only in creative work that joy may be found.

To create we must get down to bedrock. You cannot construct unless you get at the principles of construction. The principles of construction are applicable to any work. If you get away from these principles, your structure will fall down when it is put to the test. Governments have fallen because their ideas of order were not based on natural principles.

Sentiment, money, violence were not the agents in the creation of that master work of art, the flying machine. The Wright brothers had a wonderful will to comprehend natural law. Billions of dollars could not buy, blind faith could not persuade, violence could not compel the flying machine. It came with the expenditure of comparatively little money, no sentimentality, and came easily, because they went to the right source.

The first flight by the Wright brothers, December 17, 1903

We will be happy if we can get around to the idea that art is not an outside and extra thing; that it is a natural outcome of a state of being; that the state of being is the important thing; that a man can be a carpenter and be a great man. There is a book about a fisherman written by Jeanette Lee, called “Happy Island”—a very simple little book, but it is worth reading apropos, for that fisherman was a great man and had in him the secret of a great nation. I think a great nation must be a happy one.

Happy Island, by Jennette Lee

I remember a great picture—it is no larger than my two hands—it represents seven pears, and evokes everything—cathedrals, beautiful ladies. Such was the spirit of the artist that for me he projected universal essentials of beauty. In his seven pears he evidently found a constructive principle and expressed it.

The great thing lies in the little things as well as in the big. If I were to try to review the art of the past year it would be to estimate how far we have gone in this idea. But I will not try to review the art of the past year—it can’t be done—it is too near to us. We have been terribly busy with it, and it is not yet through with us. Our past is our mystery. It is the tangle we have made of our hopes when we have come up to them. The future alone is clear.

2.

No nation as yet is the home of art. Art is an outsider, a gypsy over the face of the earth.

3.

The only sensible way to regard the art life is that it is a privilege you are willing to pay for.

4.

Seldom has the great art or great science of the world been paid for at the time of creation. It has been given, and in general has been cruelly received. You may cite honors and attentions and even money paid, but I would have you note that these were paid a long time after the creator had gone through his struggles.

5.

Breadth is useless unless it effects expression. Sometimes an almost imperceptible note plays a great part in the making of a picture. It is not necessarily the obvious thing which counts strongest. The great moments of a day are sometimes such as hardly reach our consciousness, yet such moments may have made all the beauty and the success of the day. The almost imperceptible note may be the most powerful constructive agent in a whole work.

A red flower placed in a window may expand its influence over all the area of your sight.

6.

A man possessed of an idea, working like fury to hold his grip on it and to fix it on canvas may not stop to see just how he is doing the work; nor may he consider what might be any outsider’s opinion of it. He must hold his grip on the meaning he has caught from nature, and he cannot grope for ways of expression. His need is immediate. The idea is fleeting. He must have technique—but he can now use only what he actually knows. At other times he has studied technique, tried this and that, experimented, and hunted for the right phrase. But now he is not in the hour of research. He is in the hour of expression. The only thing he has in mind is the idea. As to the elegance of his expression, he cannot think of it. It is the idea, and the idea alone which possesses him, and because it must be expressed, because he has need to express it, he makes a great draft on his memory, on all his store of knowledge and past experience, and all these he regulates into service.

If later we find that there was an elegance in his expression, that there was brilliant technique, still he was not aware of it at the time of its accomplishment. It is only the sign of the success of his effort to recapture all his knowledge and make it work for him at a time of great need. He was not conscious of his gracefulness, for it was only a result of the high state of order to which he had raised himself.

A young girl may come into a room and with her thoroughly unconscious gesture bring animation and a sense of youth, health and good will. It is a fine technique which she employs, for all in the room receive her message and she imparts without loss somewhat of her youth and spirit to each one present. Her technique is handled as only a master could handle it; that is, without thinking of it. In the activities of play she has made her body supple and it readily responds to her emotion. Through gesture she has a language that is so much her own that it is spontaneous. She is young, she is healthy, and she looks on the world with a wonderful good will and there is a need within her to transform all environment to her own likeness. Her whole body, her look, her color, her voice, all about her is in service and is unconsciously ordered to express and spread the influence of the song that is in her.

If, on the other hand, she is one of those terrible creatures who must walk and talk with the airs of their betters, who must in some way pretend to be that which they are not, we may see a very skilled technique, one filled with a thousand clever tricks, but it is a self-conscious technique—one which is an end in itself. We often meet men who wear a mask of great profundity who would be bored to death in being profound.

A scientist is not a scientist in order to be a scientist. He is what he is because he wants to know about life. The scientist wants to know life—therefore the marvels of mathematics.

The young girl wants to live in the happiness of her state—therefore her buoyant gesture.

The artist wishes to declare the significances he finds in nature—therefore the painter’s technique.

There can be no delight in considering a technique that is without motive.

The simplest form is perhaps that of the juggler. Whether he catches the balls in his hands or not, the balls go up into the air, perform perfectly natural curves and fall according to the laws of nature. Whether he catches them or not what the balls do is equally beautiful. But the motive is to catch the balls, and the marvel is in the manifestation and the achievement of the motive.

A line, or a form, or a color, therefore cannot be meaningful in itself. It must have motive, and to have motive it must be related to other lines, forms and colors. It must have sequence and an end must be attained. If the end is a simple one the sequences will be equally simple. If the end is the revelation of a profound mystery of nature the sequences must be equal to it, for the revelation is written in every part of the construction.

If the technique of a master is marvelous, if it appears that he has turned paint into magic—rendered the life, the look, and all about an eye in a stroke or two—it is not that he has a bag of tricks. It is that with a mighty power of seeing the particular eye and an absolute need to express it, he uses judgment and he taps all his store of experience: the eye is not made in a stroke or two because he wants to make it in a stroke or two. He does not care how many or how few strokes it takes. The eye is what he wants.

Later he may himself marvel at the simplicity of its rendering, and other days; in the days of research, he may set himself the task of doing an eye in a stroke or two and work hard at it. It is likely that in such conscious effort he will not come anywhere near equaling the aforesaid eye, but what he will do and what he will think in this experience will sink into him and will become part of that store which must open up when again he is in the state of great need.

7.

I count on seeing your new work when you come to town, and I count on finding in it the likeness of the man I know. The techniques which are beautiful are the inventions of those who have the will to make intimate human records.

“Be a warhorse for work, and enjoy even the struggle against defeat. Keep painting, it’s the best thing in the world to do.”

— Robert Henri

8.

Be a warhorse for work, and enjoy even the struggle against defeat. Keep painting, it’s the best thing in the world to do. Learn that there are different views and that it is up to you to make your own judgments. See the value in compositional work and don’t be a life-class hack. Don’t believe that sitting in an art school and patiently patting paint on canvases will eventually make you an artist. There is more than that. If a new movement in art comes along be awake to it, study it, but don’t belong to it. Have a personal humor about things. You will never know your calibre until you have tried yourself. Avoid idle industry. Always leave out the padding. Be venturesome. Try new things that appeal to you. Examine others. Have a pioneer spirit. Prevent your drawing from being common. Put life into it. The way to do this is to see the model, see that the model is great, wonderful—a human creature there before you in the tragedy and comedy of life—then draw. Avoid mannerisms, your own and other people’s. Preserve your originality by painting what is before you as you see it, for things have a special look to you. Make your pictures of big pieces rather than small ones. Through the big pieces the statement can be made frankly and fully. Get the easy naturalness of nature. Nature is full of surprises. They happen equally in great and small events, and are inevitable results. They are parts of a sequence. Make your picture as full of surprises and as easy as nature. Don’t ever stock your head so full of “learning” that there will be no room left for personal thinking. Develop your power of seeing through the effort and pleasure of seeing. Develop the power to express through the effort and pleasure of expression.

9.

Ways of Study

The school is not a place where students are fitted into the groove of rule and regulation, but where personality and originality of vision are encouraged, and inventive genius in the search for specific expression is stimulated.

The real study of technique is not the acquirement of a vast stock of pat phrases, but rather the avoidance of such, and the creation of a phrase special to the idea. To accomplish this, one must first have the idea and then active inventive wit to make the specifying phrase. This places the idea prior to the technique as a cause for the latter, contrary to the academic idea, which is the reverse.

I am saying this with reference to the “hard grind” and “grammar” ideas. Hard grind! I was in art schools for three years before I really began the struggle with mind and body to do something with my faculties other than the sheer mechanical process of eye and steady hand assisted by several judgment-saving tools such as plumbline and stick with notches in it.

I know the “hard grind” and the “grammar” study both here and in Paris, and while I was in it I was regarded as typical, for I was anxious, and I worked all day and all evening.

From my own experience I know that “mindless drudgery” would be a better name than “hard grind,” and that “idle industry” would be equally descriptive of such work.

There are at present, all over the world, art students sitting meekly at their work copying external appearances in whatever is the fashion of the school in which they work, copying lines and tints of models of which they have no idea, no understanding, for which they have no respect, no enthusiasm, putting off to some future day that sensitive appreciation, that grasping of significance, that announcing of a special evidence of their own about the matter, simply “hard grinding!” Maybe the name is not so bad. Like a mill stone! Learning technique! Technique of what? For the expression of what? Studying construction? Construction of what? What a deception!

Those meek students, plodding away, afraid to use their intelligence lest they make mistakes, have a faith that after so much virtuous humble tint and line copying, years of it, the gift of imagination, the power to say things the world is in need of hearing for profit or pleasure and the special management of the medium, will be handed to them as a diploma is handed to a graduate.

The man who becomes a master starts out by being master of such as he has, and the man who is master at any time of such as he has is at that time straining every faculty. What he learns then from his experience is fundamental, constructive, to the point. His wits are being used and are being formed into the habit of usage.

He is working on his direct road. His “grind” is hard. His brain as well as his body is taxed to the limit, but his “hard grind” is not a dull grind. For he is grinding something. He is studying grammar because he needs it, and needing it he studies with greater wit, and knows it when he finds it.

This “going slow,” this “hard grind,” this study of “grammar” as understood in Julian’s Academy and in the academies that have sprung from Julian’s is too easy. There is not in it the “hard grind” that makes a man find himself and invent special language for his personal expression.

I am for drawing and for construction, for continued and complete study, acquirement of firm foundation. But the drawing I am interested in is the drawing that draws something, the construction which constructs. And the idea to be expressed must be at least worthy of the means.

10.

I find nature “as is” a very wonderful romance and no man-made concoctions have ever beaten it either in romance or sweetness.

Everything depends on the attitude of the artist toward his subject. It is the one great essential.

It is on this attitude of the artist toward his subject that the real quality of the picture, its significance, and the nature and distinction of its technique depends.

If your attitude is negligent, if you are not awake to the possibilities you will not see them. Nature does not reveal herself to the negligent.

As a matter of fact the most ordinary model is in reality a fascinating mysterious manifestation of life and is worthy of the greatest gifts anyone may have of appreciation and expression.

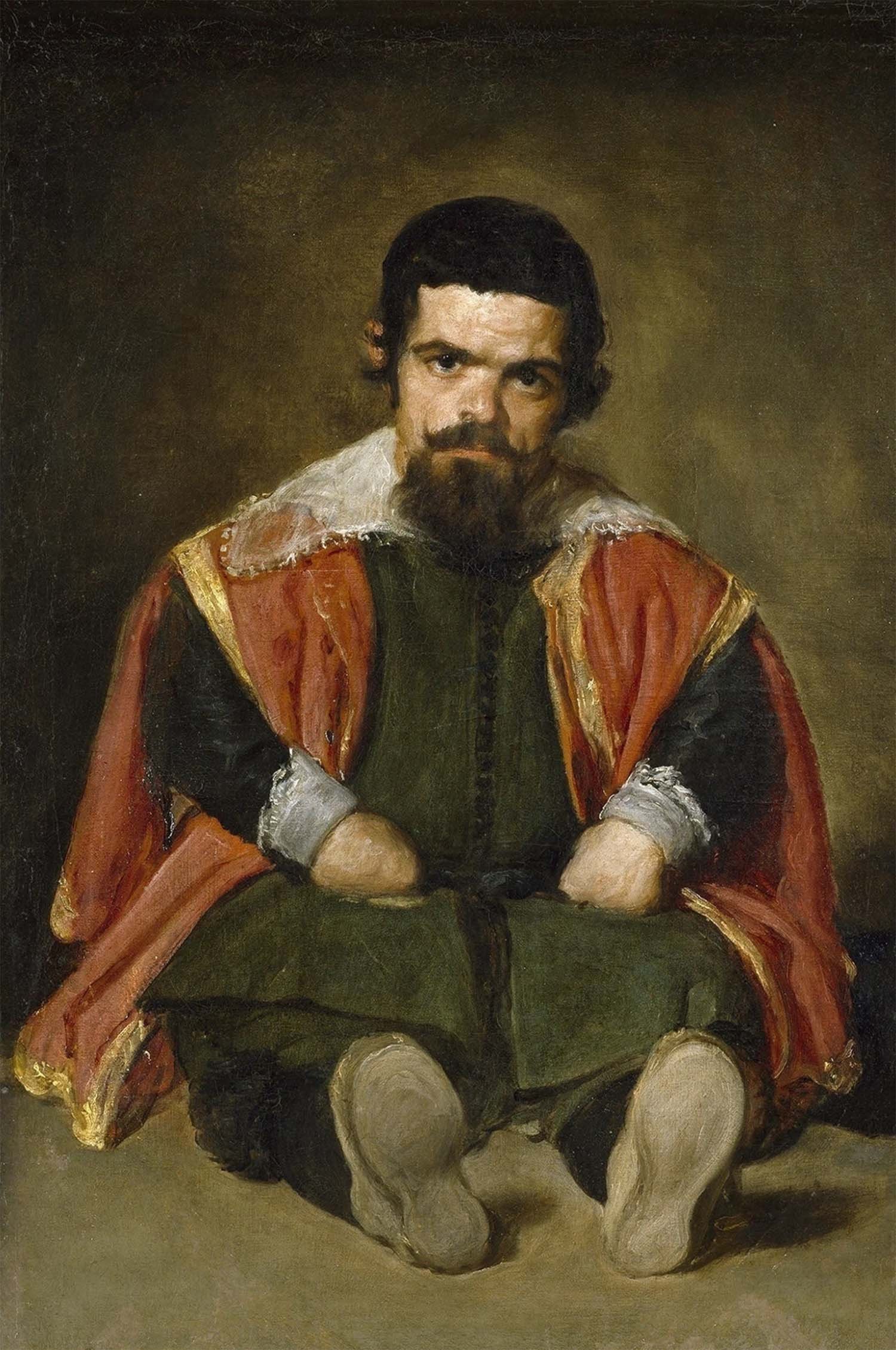

It was the attitude of Velasquez toward his model that got for him the look which so distinguishes his portraits.

The people he painted were conscious of the humanity and the respect of the man before them. They knew that he could pierce masks and that he could appreciate realities with unbounded sympathy. They undoubtedly enjoyed posing for him, and while he painted they looked at him—responded to his look—were frank with him, and revealed without pomp or negation their full dignity as human beings.

So, his king becomes a man for whom you have sympathy, pity and respect.

In that studio the king and Velasquez met and in the portrait that was painted we see eyes and gesture which tell of an unusual contract. To Velasquez he responded, and he was safe to take his true position—that of a man, not good, not bad, not great, but conscious of the futility of pomp; touched with sadness, possessed of a certain innate dignity, and craving above all things just that kind of human sympathy and respect which Velasquez, with love and without fear, was capable of giving.

Philip IV sat for many portraits to Velasquez, and it was probable that he did so because the contact meant for him his greatest moments.

There is something in environment which affects all men, causes them to live for a time in a surprising fullness, or, on the other hand, causes them to close up.

By a compelling impulse a man goes for a day in the woods. Just why the impulse came to break his usual habit he does not know clearly, rather wonders at it, but there is some vague thought of freedom. He plunges into the rough parts of the wood, climbs under and over. He runs wild. He tears his clothes—but it does not matter. The business of his progress is met with enthusiastic energy and time passes as in a dream. And concurrent with his action there is thought of a surprising fluid character. His attitude toward the life he has just stepped out of has wholly changed. Intricacies untangle. He sees people in new values. Bitter feelings have disappeared. He is over and above all petty grudges, envies or fears. Something has happened. The spirit of the wood has possessed him. He has got into rhythm. Surely he is no longer in his usual plane of life. It is a day of clear seeing.

Later, days later, in his office he cannot recall just what it was that passed—just what that ecstasy of the wood really meant, but he has a memory that he had seen into his life, and had seen it from a different angle and in a way that simplified many matters.

When the dwarfs posed for Velasquez they were no longer laughing stock for the court, and we see in their portraits a look of wisdom, human pathos and a balancing courage. Velasquez knew them as fellowmen with hearts and minds and strange experiences. He knew them as capable of sensitive approach. Even in the madman it is the glimmer of human sensibility, a groping of a puzzled heart, that makes the great moving force of the picture.

Where others saw a pompous king, a funny clown, a misshapen body to laugh at, Velasquez saw deep into life and love, and there was response in kind for his look.

The Dwarf Sebastian de Morra at the Court of Felipe IV, by Diego Velasquez

If you paint children you must have no patronizing attitude toward them. Whoever approaches a child without humility, without wonderment and without infinite respect, misses in his judgment of what is before him, and loses an opportunity for a marvelous response. Children are greater than the grown man. All grown men have more experience, but only a very few retain the greatness that was theirs before the system of compromises began in their lives. I have never respected any man more than I have some children. In the faces of children I have seen a look of wisdom and of kindness expressed with such ease and such certainty that I knew it was the expression of a whole race. Later, that child would grow into being a man or woman and fall, as most of us do, into the business of little detail with only now and then a glimmering remembrance of a lost power. A rare few remain simple and hold on through life to their universal kinship, wade through all detail and can still look out on the painter with the simplicity of a child and the wisdom of the race plus an individual experience. These, however, are rare, but the potentiality exists in practically all children. We will not see much of any of this unless the quality of our attitude is equal to it. The sky will be a dull thing to the dull appreciator, it will be marvelous to the eye of a Constable. Still-life will be dead, inert, to the eye that does not start it in motion. To a Cézanne all its parts will live, they will interact and sense each other.

All nature has powers of response. We have always been conscious of it. Our idea that things are dead or inert is a convention.

I am not particular how you take this, scientifically or otherwise, my simple motive is to make such suggestions as will bring strongly to mind the thought that the student in the school or the artist in the studio must be in a highly sensitive and receptive mood, that negligence is not a characteristic of the artist, that he must not bind himself with preconceived ideas, must keep himself free in the attitude of attention, for he can never be greater than the thing before him—which is nature, whatever else it is, and nature contains all mysteries.

Robert Henri - Artist, Teacher, Author

This concludes the part of the book, The Art Spirit, that was actually written by Robert Henri.

– Carl Olson, Jr.