The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 12

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 12

It is not easy

Paint like a fiend

The tramp sits

Use the ability

Gesture and music

To answer

I am particularly glad

From a Letter

I can think of

Letter of Criticism - 3

1.

It is not easy to know what you like.

Most people fool themselves their entire lives through about this.

Self-acquaintance is a rare condition.

There are men who, at the bottom of the ladder, battle to rise; they study, struggle, keep their wits alive and eventually get up to a place where they are received as an equal among respectable intellectuals. Here they find warmth and comfort for their pride, and here the struggle ends, and a death of many years commences. They could have gone on living.

2.

Paint like a fiend when the idea possesses you.

3.

The tramp sits on the edge of the curb. He is all huddled up. His body is thick. His underlip hangs. His eyes look fierce. I feel the coarseness of his clothes against his bare legs. He is not beautiful, but he could well be the motive for a great and beautiful work of art. The subject can be as it may, beautiful or ugly. The beauty of a work of art is in the work itself.

4.

Use the ability you already have, and use it, and use it, and make it develop itself.

Don’t just pay your tuition and drift along with the current of the school. Don’t just fall in with the procession.

Many receive a criticism and think it is fine; think they got their money’s worth; think well of the teacher for it, and then go on with their work just the same as before. That is the reason much of the wisdom of Plato is still locked up in the pages of Plato.

Make compositions. Use the knowledge you acquire in the life class at once.

Like to do your work as much as a dog likes to gnaw a bone and go at it with equal interest and exclusion of everything else.

It isn’t so much that you say the truth as that you say an important truth.

5.

Gesture and music are alike in that they have powers of extension beyond known measurements.

In looking at a great piece of sculpture—the Sphinx, we may be impressed by a sense of time. The sculptor seems to have dealt in great measures, not the ordinary ones. I believe that some such impression as this is received by most of those who contemplate the Sphinx, that it certainly does convey something outside its material self, something in very great measure. There is a peculiar feeling of awe in its presence.

In viewing the Greek sculptures there is a similar sense. The measures in the modeling are not casual external measures, but seem to be such as to convey a sense of the life within. External measures have been used therefore by the artist in their analogous sense—not in their material sense.

This may explain the great difference in impression we receive from works of different periods in art history and also the differences we feel in one artist’s work from another in spite of the fact that they may be equals in matters of skill.

In some works, marvelous though they may be, the spirit of the observer seems to be caged within the measures employed, and in other works, more marvelous, the spirit seems to be liberated into a field of other and greater measures.

In the first type of work we find ourselves caught and held in fascinating intricacies. In the second we find cause to take departure and enter into a condition of new and yet very personal states of consciousness. One catches us and shows us its marvels. The other is incentive to a personal voyage of discovery. The first type can eventually be exhausted. The second can remain as a perpetual incentive to new flights.

The men of action in the world have fixed their interests in different ways at different times, and at the same times men have taken different roads. The marvels of external beauty for one and the marvels of the internal life for the other, and in painting and sculpture the means of expression is in either case external appearances. But such different uses must they make of external appearances! It is a finding of signs.

We realize that there is no one way of seeing a thing no matter how simple that thing may be. Its planes, values, colors, all its characteristics are, as it were, shuffled before each new-comer arrives, and it is up to him to arrange them according to his understanding.

Once when I was a young student I heard another student spoke of as “one who saw color beautifully.” I was very much impressed by this. So one has not only to see color but he must see it beautifully, meaningly, constructively!—as a factor in the making of something, a concept, something in his consciousness, something that is not exactly that thing before him which the school has said he should copy. This thing of seeing things. All kinds of seeing. Dead seeing. Live seeing. Things that are mere surfaces. Things that are filled with the wondrous. Yes, color must be seen beautifully, that is, meaningfully, and used as a constructive agent, borrowed from nature, not copied, and used to build, used only for its building power, lest it will not be beautiful.

It is very hard to see this aspect, our aspect, of the thing before us. It is very hard because it is the simplest thing we do. If you could catch yourself while on some ramble in the woods and know the source of your happiness, and continuing the same kind of seeing, proceed to paint, the work you would do would be eventually a revelation to you. Eventually, I say, for at first it would shock you, so different would it be from that convention which has enslaved you. It would be your original output. The easiest thing is the hardest. It is harder to be simple than it is to be complex. Schools of new vision rise and fall. The type of that man who said he couldn’t see shadows purple but hoped soon to do so, is yet our average type.

We are not yet developed to the plane where there are many who would pit their own originality against the fashion of the day.

It is, however, to the artist or to the scientist—there are times when the distinction disappears—that we look for that freedom which will return us to simple understanding.

Our future freedom rests in the hands of those whose likeness will be in their dissimilarity, and who will not be ashamed of their own originality, whatever the fashion may happen to be.

6.

To answer, to the best of one’s ability, the questions of a child is fine teaching. This is as beneficial to the teacher as it is to the child. If the question finds the teacher unprepared he is stimulated to research on the point in question.

Many of these questions though apparently trivial are fundamental, related to the beginning of a life. The teacher participates in the study and becomes a student along with the child.

We are all different; we are to do different things and see different life. Education is a self-product, a matter of asking questions and getting the best answers we can get.

We read a book, a novel, any book, we are interested in it to the degree we find in it answers to our questions.

When the teacher is continually author both of the question and its answer, it is not as likely the answer will sink deep and get into service, as it will if the question is asked by the child.

Both methods properly used have their value, but one is much better than the other.

The special knowledge needed by one may not be much needed by another.

7.

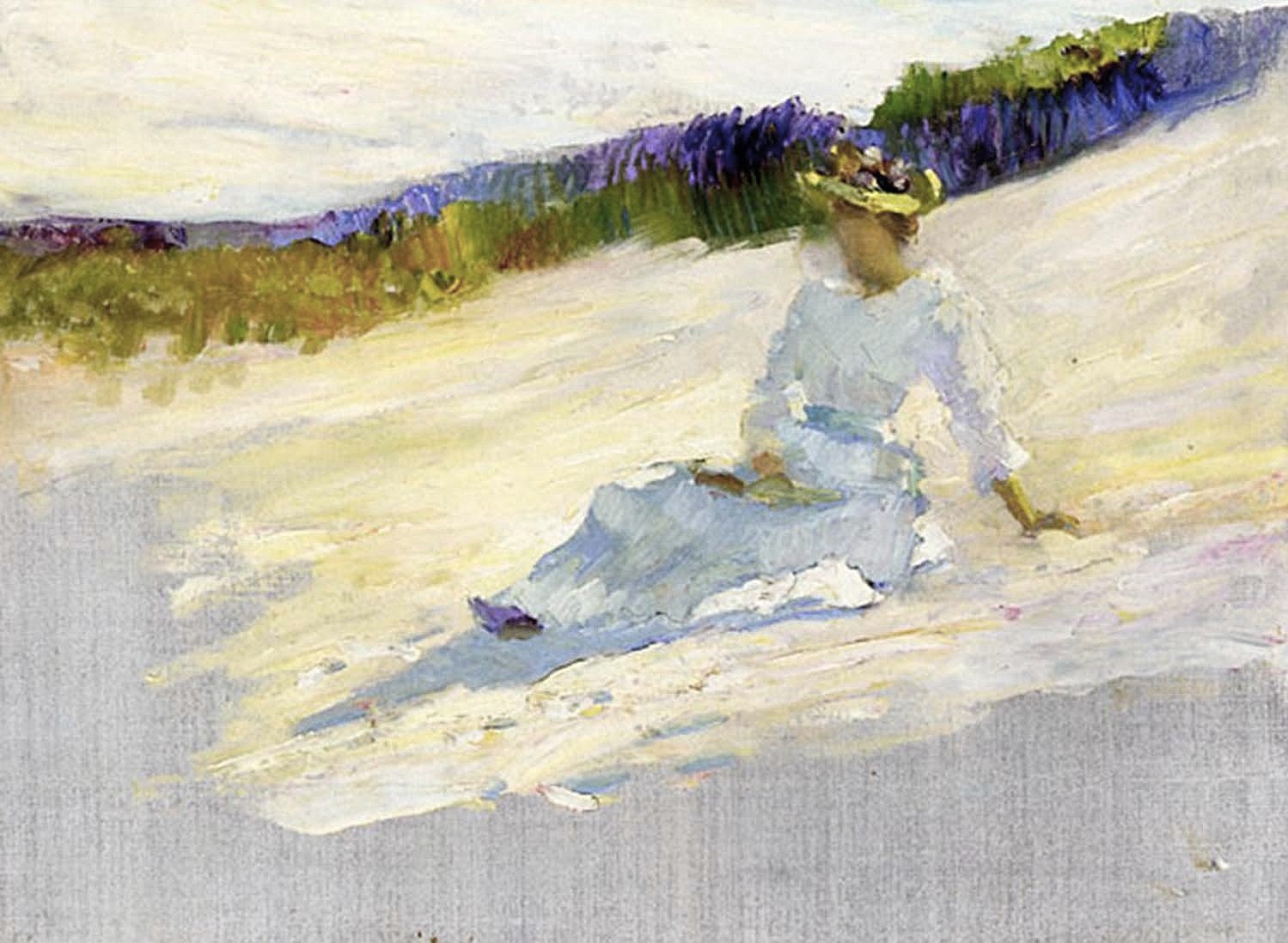

I am particularly glad to hear that you have been painting from memory. I am quite certain your best work will come from dealing with the memories which have stuck after what is unessential to you in experiences has dropped away. Of course in many of your pictures, even painted in the presence of the subject, this thing did happen.

I know one beautiful street scene you sent to the exhibition that I have always felt was done in a trance of memories undisturbed by the material presences (that is if you did do it out of doors and with the street before you).

Especially in painting brilliant sunlight, working outdoors is difficult, for it takes a long time to get eyes accustomed to the difference between light and pigment so that anything like a translation can be made.

In fact I think most pictures of the Southwest are to a great extent false because the painters get blinded into whiteness, make pale pictures where the real color of New Mexico is deep and strong.

Anyhow, all work that is worthwhile has got to be memory work.

Even with a model before you in the quiet light of a studio there must come a time when you have what you want to know from the model, when the model had better be sitting behind you than before, and unless such a time as this does come, it is not likely the work will get below the surface.

“all work that is worthwhile has got to be memory work.”

— Robert Henri

8.

From a Letter

There is great beauty in your penmanship. The flow of it. It is just such apparently unimportant tendencies toward expression of something that runs deep in one, which make drawing beautiful or otherwise.

It seems to have been Rembrandt’s very spirit which pushed the inked stick around for him, while many another appears to have been moved by intellect alone.

One of the attractions of Renoir is that at times his paint seems to have a flow, one color into and through another. One thinks of the elegance of mind that was back of the line. We seem to know the very spirit of Giotto. And the form of Manet! A beautiful dignity always in Velasquez!

It would be easy to divide artists into two classes: those who grow so much within themselves as to master technique by the force of their need, and those who are mastered by technique and become stylists.

9.

I can think of no greater happiness than to be clear-sighted and know the miracle when it happens. And I can think of no more real life than the adventurous one of living and liking and exclaiming the things of one’s own time.

10.

Letter of Criticism - 3

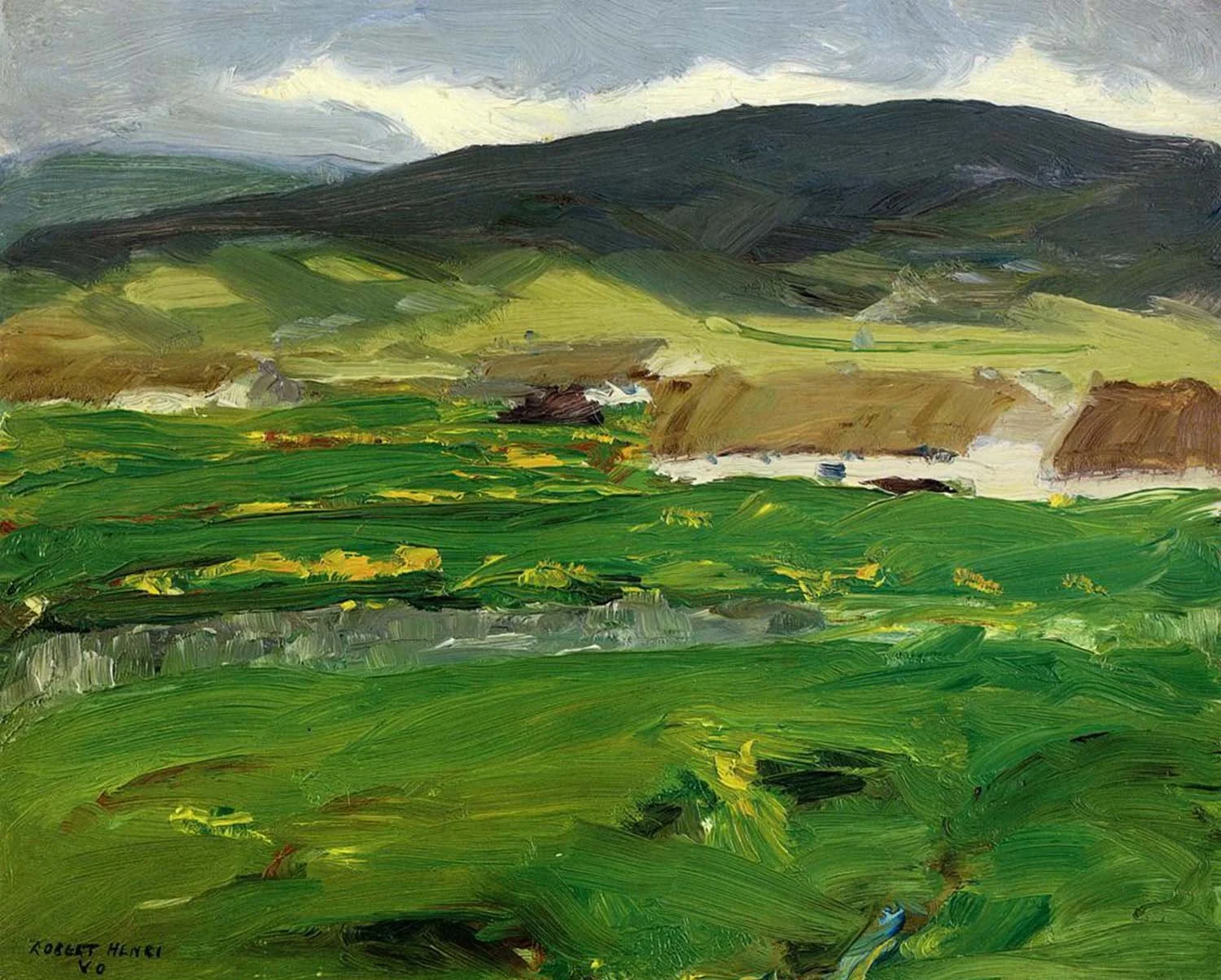

I see in the sketches a very personal outlook, an interest in the beautiful design of nature, a decided sensitiveness to the orchestration of color, good sense of form and the compositional possibilities of form.

All this I see so that the principal response I have to make is “go on.” Going on will mean a continual attack with ever the will to get the fullest conclusion, to make every work as complete as possible. By “complete” I do not mean any conventional finish, but I do mean a complete statement of just what you feel most important to say about the subject.

A work of art is not a copy of things. It is inspired by nature but must not be a copying of the surface. Therefore what is commonly called “finish” may not be finish at all.

You have to make your statement of what is essential to you—an innate reality, not a surface reality. You handle surface appearances as compositional factors to express a reality that is beyond superficial appearances. You choose things seen and use them to phrase your statement.

When I opened the package and set out the five panels, I had a decided satisfaction in them. The sense of beauty was refreshing. No. 3 caught me first.

No. 4 seems not to have the fine areas, weights, measures, variety, balance of the one thing against another as in No. 3, where the measures are excellent, giving those qualities called distance and atmosphere.

I find the white house a bit big for the other forms of the composition, big to be so empty. The incidents of door, windows, fence, roof and chimney do not seem sufficient to take away from the baldness of this large and prominent area of the house.

With an area so large and prominent, which attracts so much, there should be more interest to warrant the attraction. This interest might be produced in many ways. Variation in color, in light and dark, etc. The green tree to right is to me the finest incident in the composition. This has life. One does not stop in seeing it. There is an engaging variation.

In sound there may be monotony—one note prolonged to infinity.

There may be variety.

Variety may be a devilish jangle.

Variety may be such as to produce a popular air.

Variety may be such as Beethoven employed.

Good composition in painting is equally a fine employment of measures.

Compare your painting of the things of No. 4 with those of No. 3.

Does not each thing look more precious in No. 3? Compare white house with white house, window with window, incidental stave, stick or other interruption with each other. You will find them all functioning, alive, interesting in No. 3. It is only in that tree in No. 4 that one feels an equal life. The why of this is that there is coördination in No. 3. The things are parts of a whole. Each thing benefits the whole, its neighbor, all its neighbors, and is receiving benefit from all of them. This is the principle of order. Each thing is more than itself alone.

In the great compositions of sound, the notes have a power beyond what we might have hoped for them. They enrich their surroundings and are enriched by their rich surroundings.

In the efforts to accomplish composition there are many rules and schemes established, some of them good and some of them bad. But one thing I am certain of, and that is that intense comprehension and intense desire to express one whole thing is necessary. Without a positive purpose, means effect only an exercise in means.

You can’t know too much about composition. That is; the areas you have to fill, their possibilities, but you must, above all, preserve your intense interest in life. You must have the will to say a very definite thing. Then, the more you know your means the better.

I put a different meaning to the words things and forms.

“You can’t know too much about composition.”

— Robert Henri

I once had a pupil whom I considered an artist, and he was an artist despite the fact that he never drew the model in even reasonable anatomical proportion. This was too bad, but the proportions of the forms in their areas on the canvas, the proportions and “steps” made in his colors, values, lines, were beautiful. He was remarkable in expressing with what might be called form proportions, and not at all good in expressing with thing proportions.

You have surely a sense of beauty and romance in reality. You do not have to soften and sweeten nature to make it beautiful. You are plainly not of the sort who think a work of art or a thing beautiful must be a cheat. You like nature, do not feel that you have to apologize for it, and you believe in its integrity, you like integrity. You think nature is all right, that there are endless, inexhaustible pleasures, and revelation in it. You believe that it is worth while getting frankly acquainted with, and that it is worth while trying to tell about the deepest intimacies of this acquaintance, to tell in paint, or in any other way, in fact. Your work tells me this much, because perhaps I am looking for it, anxiously expecting and desiring it in all work, and because I am used to pictures. That’s the reason I say “go on.” I do not say “go differently.” You have to go on satisfying yourself more and more in order that others less keen to see and less used to reading pictures will get the song you sing. Your only hope of satisfying others is in satisfying yourself. I speak of a great satisfaction, not a commercial satisfaction.

There are people who buy pictures because they were difficult to do, and are done. Such pictures are often only a record of pain and dull perseverance. Great works of art should look as though they were made in joy. Real joy is a tremendous activity, dull drudgery is nothing to it. The drudgery that kills is not half the work that joy is. Your education must be self-education. Self-education is an effort to free one’s course so that a full growth may be attained. One need not be afraid of what this full growth may become. Give your throat a chance to sing its song. All the knowledge in the world to which you have access is yours to use. Give yourself plenty of canvas room, plenty of paint room. Don’t bother about your originality, set yourself just as free as you can and your originality will take care of you. It will be as much a surprise to you as to anyone else. Originality cannot be preconceived, and any effort to coddle it is to preconceive it, and thereby destroy it. Learn all you can, get all the information that is within your reach about the ways and means of paint.

The best advice I have ever given to students who have studied under me has been just this: “Educate yourself, do not let me educate you—use me, do not be used by me.”

What I would say is that you should watch your work mighty well and see that it is the voice that comes from within you that speaks in your work—not an expected or controlled voice, not an outside educated voice.

In the No. 2 there is beauty of open space, an expression in the temperature. There’s a good overall state of being in that landscape, and then that fence is beautiful in its color, it progresses.

You need not know a thousand tricks performed by others, you need not have a great stock of tricks of your own making. With a great will to say a thing comes clairvoyance. The more positively you have the need of a certain expression the more power you will have to select out of chaos the term of that expression. Your sense of color I am sure of. I think you see color in beautiful order in nature. You see color in construction. Some people only see color and more color. The great thing is what happens between colors. Some eyes see how lines go over a shoulder and over a hip, can copy them and make an indisputably honest statement of them; another eye may see the relation between them, will recognize them as powers in a great scheme.

I think you can have a wonderful time. It is really a wonderful time I am wishing you. Art is, after all, only a trace—like a footprint which shows that one has walked bravely and in great happiness. Those who live in full play of their faculties become master economists, they understand the relative value of things. Freedom can only be obtained through an understanding of basic order. Basic order is underlying all life. It is not to be found in the institutions men have made. Those who have lived and grown at least to some degree in the spirit of freedom are our creative artists. They have a wonderful time. They keep the world going. They must leave their trace in some way, paint, stone, machinery, whatever. The importance of what they do is greater than anyone estimates at the time. In fact in a commercial world there are thousands of lives wasted doing things not worth doing. Human spirit is sacrificed. More and more things are produced without a will in the creation, and are consumed or “used” without a will in the consumption or the using. These things are dead. They pass, masquerading as important while they are before us, but they pass utterly. There is nothing so important as art in the world, nothing so constructive, so life-sustaining. I would like you to go to your work with a consciousness that it is more important than any other thing you might do. It may have no great commercial value, but it has an inestimable and lasting life value. People are often so affected by outside opinion that they go to their most important work half hearted or half ashamed.

“What’s the use of it if you are not making money out of it?” is a too common question. To what distinction an artist’s labors are raised the moment he does happen to make money out of them! Very false values. I say this and I know as well as any the difficulties of making sufficient money and the necessity of making it in order to live and go on.

Go to your work because it is the most important living to you. Make great things—as great as you are. Work always as if you were a master, expect from yourself a masterpiece.

It’s a wrong idea that a master is a finished person. Masters are very faulty, they haven’t learned everything and they know it. Finished persons are very common—people who are closed up, quite satisfied that there is little or nothing more to learn. A small boy can be a master. I have met masters now and again, some in studios, others anywhere, working on a railroad, running a boat, playing a game, selling things. Masters of such as they had. They are wonderful people to meet. Have you never felt yourself “in the presence” when with a carpenter or a gardener? When they are the right kind they do not say “I am only a carpenter or a gardener, therefore not much can be expected from me.” They say or they seem to say, “I am a Carpenter!” “I am a Gardener!” These are masters, what more could anyone be!

I like your work and have only to ask you to go on your own interesting way with all the courage you can muster.