The Art Spirit By Robert Henri

Chapter 13

The Art Spirit

Robert Henri

Chapter 13

Keep as far as possible

Technique must be solid

Letter of Criticism - 4

Letter of Criticism - 5

In the faces painted

Nature is sometimes seen through

It is a big job

Letter From New Mexico

1.

Keep as far as possible all your studies, all your failures, if somewhere in them appear any desirable qualities.

Such canvases are good for reference.

Later study of the work recalls the good of it.

Sometimes an old unfinished canvas will serve as a recall from lesser and unimportant wanderings.

You can learn much from others but more from yourself.

In looking at an incomplete canvas some time after its doing, the whole thing becomes clear, the tangle dissolves, and you see the way to complete it and how certain faults may be avoided.

Don’t be ashamed to keep your bad stuff. After all you did it. It is your history and worth studying.

Shame makes a small man give up a lot of time smearing over and covering up his rough edges.

There is a wonderful work of art by Leonardo da Vinci, one of his most interesting. It is quite unfinished, yet perhaps it is one of his most finished, gets us in deeper. No work of art is really ever finished. They only stop at good places.

Shame is one of the worst things that ever happened to us.

There is weakness in pretending to know more than you know or in stating less than you know.

2.

Technique must be solid, positive, but elastic, must not fall into formula, must adapt itself to the idea. And for each new idea there must be new invention special to the expression of that idea and no other. And the idea must be valuable, worth the effort of expression, must come of the artist’s understanding of life and be a thing he greatly desires to say.

Artists must be men of wit, consciously or unconsciously philosophers, read, study, think a great deal of life, be filled with the desire to declare and specify their particular and most personal interest in its manifestations, and must invent.

Exhibitions will never attract crowds or create any profound interest until there is in the works exposed evidence of a greater interest in the life we live.

3.

Letter of Criticism - 4

The most important thing I can say to you is that your work shows the artist temperament; the tendency to produce impressions of life, as you find it fascinating, through the mediums of drawing and color.

All your things suggest action, or, better still, the state of mind which is the cause of action.

You have the gift of color. Look at Japanese prints. You will see in them these gifts developed to completion. The color is benefited by the form. The form is benefited by the color. They balance. They seem sufficient. There is no haste, yet they are as fast as one could desire them to be.

They are impressions of nature, often similar to yours. But they fill and satisfy. They have the sense of full completion.

The Japanese artist had no hurry to get away from the work lest it go wrong. He faced it out, and won out.

I would not have your drawings take on the conventions, but I would have them acquire the solid integrity, the certainty, of the Japanese prints.

Your Children with the Balloons (No. 1) is beautiful in color, in child action. The balloons appear to have been painted through the wondering eyes of the child. The balloons are as admirable as the child saw them.

Should they have more completion? I believe that it is not in the balloons themselves that further completion should be sought, but it should be in establishing a finer relation in all the parts of the composition to the space of the whole.

Probably it would be good to say to you: Consider the whole space of your canvas as the field of your expression. A fine adjustment must be made within its limits. Your ideas must not wander, anywhere, within the confines of the canvas, but they must fill it completely.

A space may be left bare, but that bare space must become meaningful. It is a part of the structure nevertheless.

In the picture of the two women in the rain (No. 2) there is the look and the feel of a shower pouring down beautifully. The lines with which you have indicated the rain appear to have an easy haphazard look. But they cannot be haphazard for they have a fine rhythm and they do make me follow you into the spirit of rain. They have the science of design in them and the science is, as it should be, beautifully covered.

The Portly Lady (No. 3) with the market basket has the fascinations of Renoir color, and the humor of her shows your kindly spirit. This may be said of practically all your figures.

Courage to go on developing this ability to see in nature the thing which charms you, and to express just that as fully and completely as you can. Just that. Nothing else. Not to do as any other artist does. Nor to be afraid that you may do as any other artist does.

Do not require of your work the finish that anyone may demand of you, but insist on the finish which you demand.

When the thing suits you it is right. Your greatest masterpiece may be even more slight than any of these things you have shown. Even more sketchy. But the order in the slight material you will use will be so positive, so certain and all comprehending that the fullest sense of your idea will be conveyed and it will be complete.

The most beautiful art is the art which is freest from the demands of convention, which has a law to itself, which as technique is a creation of a special need.

The demand we so often hear for finish is not for finish, but is for the expected.

Judging a Manet from the point of view of Bouguereau the Manet has not been finished. Judging a Bouguereau from the point of view of Manet the Bouguereau has not been begun.

I have just placed six more of your pictures before me. One need not bother you talking of color. You need but to command your medium and your sense and pleasure in color will do the rest. With an actual command of the medium, which you must work for, you will make beautiful things. In No. 4 the white is exquisite. But the seated figure is an ogre from lack of sustained intention.

No. 5. Beautiful in color and gesture and space relation of the figures.

No. 6. Again the beautiful relation of figures. They are in charming sympathy with each other.

No. 7. Interesting for the strident action and color.

No. 8. An excellent thing. Except that the table rests uneasily on its legs this canvas has the quality of relationship within its confines that gives to the whole a real integrity. Its spaces organize and one space illuminates the other. It has that largeness which we admire in the lithographs of Daumier.

No. 9. Altar boys. The allegro and the pomp. Such an excellent boy to our side of the priest. What fine work you can do in this vein when your grip is stronger, when you can go the step of greater assurance. It will do well for you to look at Daumier’s lithographs. His fancy is free. His statement is assured.

In the color of your No. 10 one imagines the voices in the air.

No. 11. A beautiful background.

No. 12. Charming color. Had you more security in your idea of the figures, which would have made you draw them hardly different, yet with more positiveness, this would be a splendid composition.

No. 13. Again the color, air, space, gesture of woman’s head. Too bad she has such short fat legs; and that the ground is not substantial. By substantial I do not mean heavier, darker, nor this nor that, but simply had you considered it more as ground on which a woman walks, your feeling would have dictated the means of its substantiality.

Your drawings also show the artist in you. You are interested. You have art. What you say is as though it came from you. It is a personal interest of your own and it interests me.

You have a big line. It often gets cramped, but the big line is there and it can grow.

Daumier and the Japanese prints can be a good influence on you because you need not do like them.

I have just noticed the backs of two little girls walking away. But there are so many I might notice. A woman in red with another at her side. Little children walking parade. Children at a door. Fat party in cab. Groups of people. Foot bath. Sweepers. Fashions. People drooping in the rain. Women and children. And so forth, and so forth. All interesting matters of wit.

My best use to you is that I appreciate these things. And my present appeal to you is to go on telling us what you like, giving us your delight in it all. It is the way the best artists have made themselves.

In going over these slight works of yours I have had a great pleasure. They might have been much heavier without having as much weight and I might not have had any pleasure at all.

4.

Letter of Criticism - 5

It is the conception which dictates the form and the color. The world and life are common, every day, and almost empty to a great many people, but there are those who see that the world and life are mysteriously wonderful.

There is a latent possibility of specific and penetrating vision in each individual. The thing is to develop this possibility. The artists who count develop their vision, and the results, since each one is different from the other, are surprising and important.

I would call your attention to the reproductions of those children’s heads done by Renoir. They are easily obtainable and they are very beautiful, even without the Renoir color. To have done such work Renoir must have been charged with a high estimate and a great reverence for the child, an unsentimental but a just appreciation of the wonder before him; and he must have been so charged at the very moment of the execution, for thus his hand was guided to a magic that makes his interpretation so wonderful.

In suggesting the works of masters, I do not mean that pictures like their pictures should be made, or that motives like their motives should be repeated. But I point rather to the principles which underlie their work. The principles of developed judgment, power of essay, power of intense feeling, intense respect.

Rembrandt’s beggars are wonders of life. He did not pass them on to us saying simply, “They are vulgar fellows.”

Besides this principle of motives, there is the principle of construction. The construction with paint on flat canvas of colors and forms, for the expression of ideas. The mastery of these mediums, understanding of limitations and possibilities within the borders of the canvas, and with the materials used.

And these two; the motive and the means must be so brought together, so enacted at the same time, that their action is as one.

It will not do to have your fine thought yesterday, and paint your picture today.

I advise the study of the works of the masters. Titian is a good one, for he understood organization, as his works demonstrate, and he happens to be available in many reproductions. Observe his compositions of figures and his portraits of men and women. See how much use he makes of balances and rhythms. Study these things well. Look for the way the pictures are laced and bound together by their lines, how they flow in currents which control your sight and your interest. See the masses of light so held in size in spite of de- tail, and the masses of dark, all of such weights and such measures that there is fullness, sufficiency.

Good painting is a result of effort to obtain order, and the order must go to all the sides of the canvas. Thus serene dignity, static repose, vitality, action, variety, and the various states of life can be suggested.

The exclusion of the trivial must be effected.

I am not considering so much either the merits or demerits of your present work. I am trying to say things that will be useful to you just as though I were saying them to myself—for they would, and I hope will, be useful to me.

5.

In the faces painted by Greco we get something of what was real—what happened in Greco. Novels are sometimes more historical than histories.

We read books. They make us think. It matters very little whether we agree with the books or not.

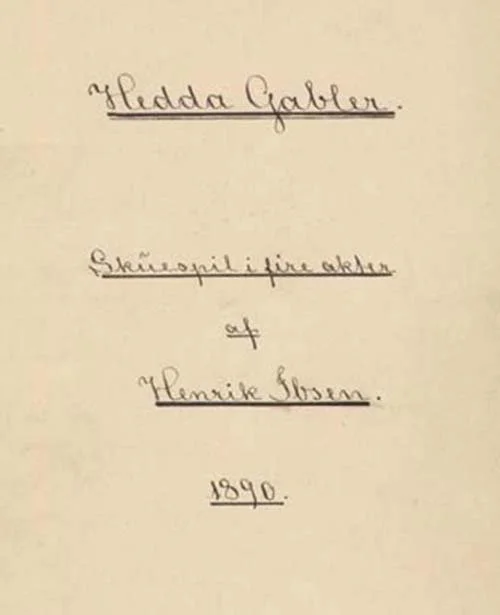

Ibsen clearly identifies his characters. These characters, however, are merely his materials. It is not Hedda Gabler he introduces to us. It is a state of life and questions as to the future of the race.

Today we do not know how much we owe to Shakespeare. His work is no longer confined in his writings. All literature has been influenced by him. Life is permeated with the thoughts of Plato, with the thoughts of all great artists who have lived. If you are to make great art it will be because you have become a deep thinker.

6.

Nature is sometimes seen through very obscure evidences.

7.

It is a big job to know oneself, no one can entirely accomplish it yet—but to try is to act in line of evolution. Men will come to know more of themselves, and act more like themselves, but this will be by dint of effort along the line of humble self-acknowledgment. Today man stands in his own way. He puts a criterion in the way of his own revelation and development. He would be better than he is and because man judges poorly he fails to become as good as he might be. He should take his restraining hands off himself, should defy fashion and let himself be. The only men who are interesting to themselves and to others are those who have been willing to meet themselves squarely. The works of the masters are what they are because they are evidences from men who dared to be like themselves. It cost most of them dearly, but it was worth while. They were interesting to themselves, and now they are interesting to us.

8.

Letter From New Mexico

Here in the pueblos of New Mexico the Indians still make beautiful pottery and rugs, works which are mysterious and at the same time revealing of some great life principle which the old race had. Although some hands lead, the whole pueblo seems responsible for the work and stands for their communal greatness. It represents them, reveals a certain spirituality we would like to comprehend, explains to a degree that distinction which we recognize in their bearing.

Materially they are a crushed out race, but even in the remnant there is a bright spark of spiritual life which we others with all our goods and material protections can envy.

They have art as a part of each one’s life. The whole pueblo manifests itself in a piece of pottery. With us, so far, the artist works alone. Our neighbor who does not paint does not feel himself an artist. We allot to some the gift of genius; to all the rest, practical business.

Undoubtedly in the ancient Indian race, genius was the possession of all; the reality of their lives. The superior ones among them made the greater manifestations, but each manifested, lived and expressed his life according to his strength; was a spiritual existence, a genius, an artist to his fullest extent. Apart from that, they raised crops, covered themselves, attended to the material according to their understanding, and wandered of course afar into that dark life outside the artist life, into war and strife, and all the fruits of material greed—like ourselves.

Behind them they have left some records of both existences, but we cherish most those which tell of a certain spiritual well-being, the warm heart in love with life and working with a love of work which is the song of their well-being.

In America, or in any country, greatness in art will not be attained by the possession of canvases in palatial museums, by the purchase and bodily owning of art. The greatness can only come by the art spirit entering into the very life of the people, not as a thing apart, but as the greatest essential of life to each one. It is to make every life productive of light—a spiritual influence. It is to enter government and the whole material existence as the essential influence, and it alone will keep government straight, end wars and strife; do away with material greed.

When America is an art country, there will not be three or five or seven arts, but there will be the thousands of arts—or the one art, the art of life manifesting itself in every work of man, be it painting or whatever. We will then have to give in kind for what we get. And every man will be a true enrichment to the other.

Any step toward such an end is a step toward human happiness, a sane and wholesome existence. Much will come of the effort. There will be failures as well as successes, but if the strong desire exists both conditions will serve as experience in progress.